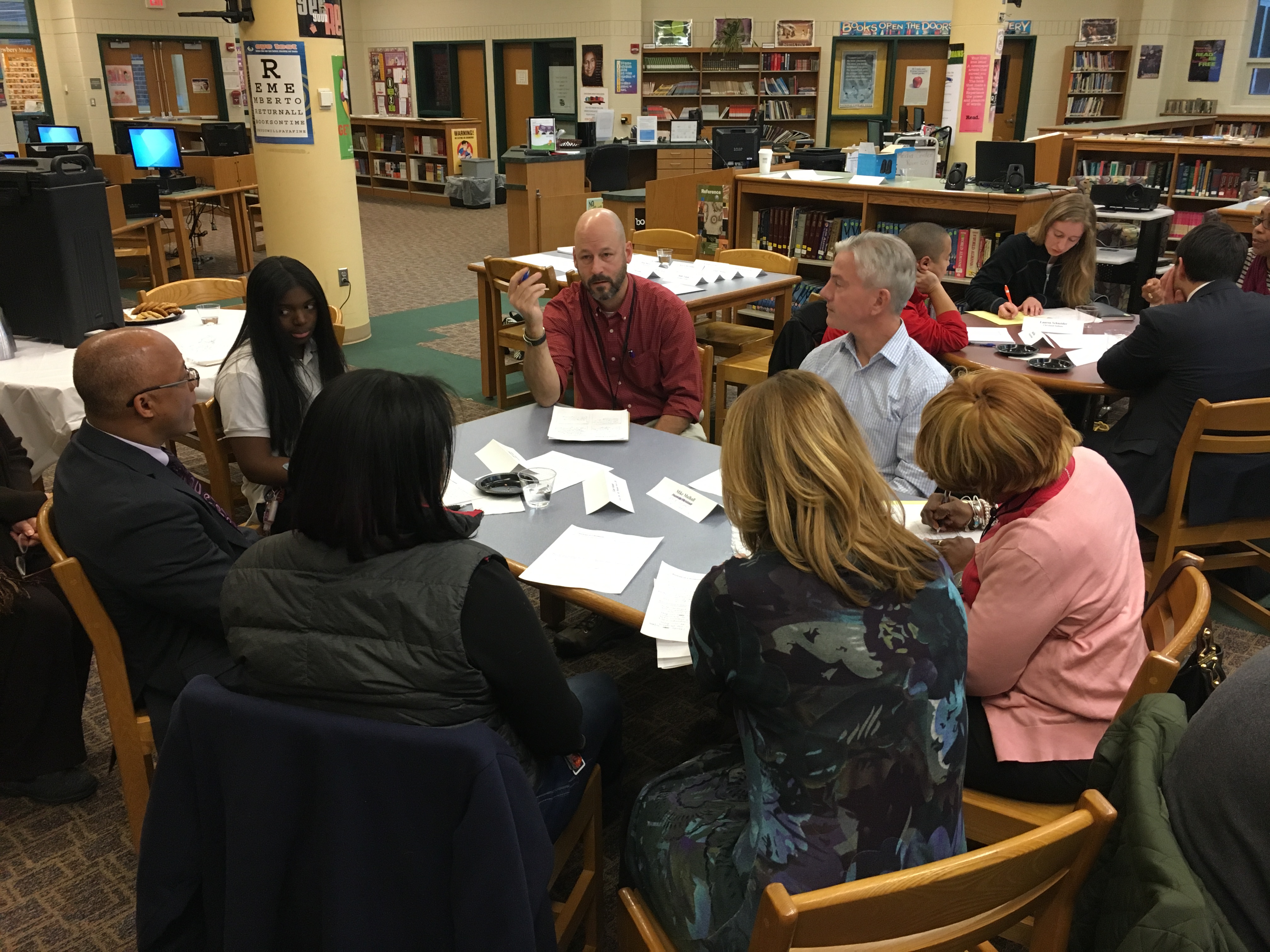

Advisory Committee for the John Adam’s College & Career Academy at work.

Cleveland Metropolitan School District’s (CMSD) portfolio strategy was launched in 2006 in an effort to support a range of high-quality school choices across the city.

At Springpoint, we’ve partnered closely with CMSD as they design and launch new high schools to best serve their students. The process of new school design has driven innovation in the district, leading to approaches like mastery-based learning and, importantly, community-driven school model design.

As CMSD gears up to launch six new high schools this summer, they are doubling down on their commitment to community input, finding even better ways to engage stakeholders. We sat with Angee Shaker, Executive Director of Portfolio Engagement, to talk about what CMSD has learned in their community collaboration work. We hope these rich learnings can help schools and districts who are trying to authentically and inclusively involve community members—from 8th-grade students to innovative business leaders—in school design.

Angee Shaker, Executive Director of Portfolio Engagement, Cleveland Metropolitan School District

Can you describe how you involve the community in school model design?

We think about our community collaboration work broadly. The main mechanism is an advisory committee—one for each school—that meets in advance of a school’s launch. Each committee includes the principal/design leader, district support staff, parents, and students. We also invite external community members like faith-based leaders, business leaders, philanthropic partners, and potential partners. Transformative change requires transformative relationships.

These meetings are explicitly student-centered—if we start to trail off we always bring it back to our young people. To do this, we ground our work in the “why,” looking at data and talking about the problems we’re trying to solve. Then, we pose a series of important questions to the group: What are your hopes, dreams, and fears as we begin to go down this process? How can we make school more relevant, meaningful, and engaging for students?

This engagement builds understanding and trust in the community and allows schools to be more open and transparent. It also helps teachers open up to deeper opportunities stemming from these close partnerships with the external community.

How do you make sure all key stakeholders have an equal and impactful seat at the table?

It is important, first, to establish norms for our committees to ensure equitable stakeholder contribution and mitigate tensions. For example, we expect all participants to show up (on time) and contribute, and we expect and build a level of trust and respect throughout each session.

We also ensure that participants understand the process as well as the goals and objectives. For external community members that means clearly explaining the nuances of this work. Operating a school is not easy. Including external stakeholders in the process lets them understand how complex this work is and grasp the magnitude of what principals and teachers are facing.

We also create a set of norms that lay the groundwork for equitable and fruitful discussions. During our break-out sessions—and throughout the brainstorming process—we constantly check for engagement. We work one-on-one with each student to help them feel comfortable and prepared so they’re empowered to speak up in large groups. Inviting their parents often helps with this too!

Providing different contexts for sharing is another approach we use, such as small groups and pairs for those who feel more comfortable collaborating in those ways. We also started doing exit tickets following sessions, which lets us survey each participant to ensure we’re all on the same page and no one feels left behind.

How does this collaboration lead to deeper community partnerships?

Collaborating with the community invests our stakeholders in new school design work—and ultimately in the new schools themselves. For example, when we were designing Lincoln-West School of Science & Health (LWSSH), we had a commitment from the MetroHealth System early on. They wanted to get more Cleveland public school graduates into their talent pool, particularly as the health care field expands. We invited MetroHealth staff and leaders to the table from day one. Their passion for student success doubled because they now had skin in the game. They now have a very deep partnership with the school—LWSSH students take classes inside of the actual hospital, learning closely from staff and pairing up with mentors who specialize in areas where students demonstrate interest.

At Rhodes School of Environment Studies, leaders from the Cleveland Metropolitan Zoo served on the school’s advisory committee. This has sparked conversations about how a mutually beneficial partnership could work. As a result of these brainstorming discussions, a three-year grant was issued to support Conservation Leadership courses. These courses will include year-round coursework using wildlife conservation as the theme, and culminate in students implementing community leadership projects connected with the Zoo’s conservation programs. Fostering partnerships early and keeping folks engaged will pay off for our kids.

Another example was at Lincoln-West School of Global Studies where we knew there’d be a focus on language, culture, and global and local social movements. We invited the Cleveland Council on World Affairs (CCWA) to join the committee, which led to a deeper partnership involving exposure, research, and networking opportunities through guest speaker appearances that dovetail with the curriculum. For example, CCWA recently hosted a foreign policy forum with Ambassador John Maisto who talked about the very distinct economic and political challenges facing both Venezuela and Columbia. Students researched the speaker in advance, the current context of Venezuala and Columbia, and developed a list of questions for the speaker.

What is one thing that you have learned doing this work?

In the past, we tried to do too much. We heard from participants that they needed more time for relationship building and to digest and carefully reflect on the student data. This led us to scale back on the deliverables. This year, we’ve been focusing on the two most important elements: a Portrait of a Graduate tool, which aligns design teams around the skills and knowledge graduates should have after four years at the school—and the guiding principles, which capture the values and traditions of the communities being served. This has also left more time for conversations that surface interesting insights and stronger foundation setting for the new school model. And participants didn’t feel as rushed as in previous years. Everyone has a contribution to make and the more diverse the group is, the more we learn from each other. The people who volunteer their precious time to do this type of visioning work are passionate about their community and have high expectations for the schools within them. When we tap into that passion, that’s when hearts and minds open and up and the ideas flow. It’s a process that shouldn’t be rushed if you can avoid it.

Advisory Team engaging with Campus International K-8 families to capture their hopes and dreams for the new Campus International High School.

How do you continue this work and keep the community invested after schools launch?

Community member participation early in the process can fuel their continued support. A couple of ways we ensure that the schools don’t lose sight of their Portrait of a Graduate or Guiding Principles is by inviting our Advisory Teams to participate in our bi-annual progress updates with the principal. The principal shares examples of how the design principles are carried out in the day-to-day activities and rituals at the school.

Also, after the school is up and running, an Advisory Board is formed to offer insights, advice, and feedback on issues critical to the school. Sometimes Advisory Committee members go on to serve on the Advisory Board.

What continues to be a challenge this year?

We are set up to launch a total of six schools, which is atypical. Previously we’d focused on two or three at the most, which allowed us to follow up personally with people regarding scheduling and deliverables. It’s been harder to have those personal touch points with people this year because of the sheer volume. But we’ve learned some useful lessons in this cycle of work, which will undoubtedly help us in future years, as well as in iteration cycles of our school design work going over the long term.

What is one thing that surprised you?

I’ve seen people have the most amazing transformations. Like business leaders who walk away with a deeper understanding and respect for teachers and principals and a hunger to become even more deeply involved. Or teachers who start out a little resistant to new ideas and evolve into champions of the work after a robust problem-solving session with the committee. Bringing so many stakeholders to the table with their different perspectives creates smarter designs that are more likely to work well inside a school.

Do the committee members feel like they are heard? How do you know?

The committees have a strong voice in leading the conversation. For instance, one group was interested in mastery-based learning but didn’t really understand how it looked in a practical setting. We offered school visits to participants and also brought in our mastery specialist, Kristen Kelly, to explain mastery in depth because they wanted to learn more. We are equally diligent about adapting to the needs of the committee as we are about staying on task.

What is one thing you learned that you wish you knew earlier?

This year, some of our committees included 8th graders (in addition to high school students) who will attend the high school we’re designing once it opens. These students had a very unique perspective because they could actually see themselves in the school—they were engaged, vocal, and thoughtful. We even brought them to the high school choice fair where they described the school and its mission to their peers. They knew the vision inside and out, and their excitement was contagious.

I was initially worried that these students might be too young or too shy to engage with the adults, but I was delighted and energized by their enthusiasm, ideas, and contributions. We plan to do this for our community collaboration work moving forward.

—

How does your school or district engage in the wider community in school design? How have community partnerships developed to support students? Let us know on Twitter or shoot us a note: info@springpointschools.org